We all want to run faster, more efficiently, with less effort and without the risk of injury. There are many things you can do to improve your running technique, like work on your cadence.

What is cadence

Cadence (or cadence) is the number of steps a runner takes in one minute. Cadence is one of two factors that determine a runner’s speed (the other is stride length).

Advanced runners have a higher stride rate because they tend to run faster than beginners. Elite athletes run at a cadence of about 180 strides / min or more, while for most amateurs the cadence will be 150-170.

Is there a one-size-fits-all cadence?

The oft-cited “perfect cadence” was described by coach Jack Daniels as 180 steps per minute. Daniels noted that elite runners typically run 180-200 steps per minute.

For example, on his way to his 2:03:59 world record at the 2008 Berlin Marathon, Haile Gebreselassie ran at 197 strides per minute.

Subsequently, 180 steps / min became a kind of “philosophical stone” for amateur runners and the indicator to which they strive. But not everything is so simple.

At different speeds, the cadence will also be different. The optimal cadence varies from runner to runner and at different paces. For example, the cadence of the same athlete during jogging will be 160 steps, and in tempo training it may well be above 180.

There is no single cadence norm that everyone should strive for: the optimal cadence for each runner is based on many things, including current pace, height, weight, leg length, and running ability.

But while there are no general guidelines, tracking cadence and working to increase it has many benefits: it can help you improve your running performance, reduce your risk of injury, reduce muscle damage during training, and improve your running performance.

Why cadence matters

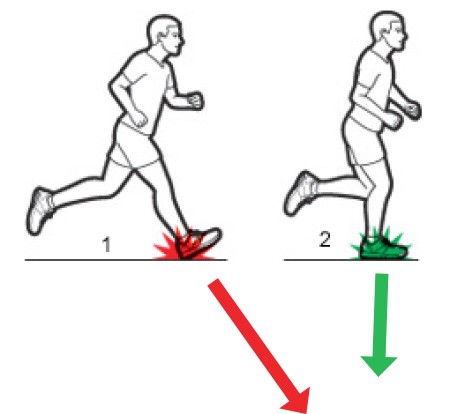

If your stride rate is low, it could mean that you are taking large strides, landing in front of you and slowing down your forward movement. This creates more strength upon landing, slows you down and puts more stress on your bones and joints.

Biomechanically, the slower your stride frequency, the more work your body does with each stride. The faster the stride, the “lighter” it is: By reducing the time you hit the ground, you minimize the amount of work your body has to do for each kick, thereby reducing the risk of injury while running.

With the correct running technique, landing occurs closer to the center of gravity. This is ideal because landing in this way puts the least impact on the body. Increasing your stride is one way to do this, but in the long run, you should also work on muscle strength in your legs and improve your running technique.

How to measure your cadence

The first step to increasing cadence is determining your current cadence. It will depend on the type of workout you are doing. During speed work, the frequency is likely to be higher than during recovery or long runs, so it makes sense to measure cadence during all types of workouts.

To do this, simply count your steps for 30 seconds and then double the number. Take a few measurements to make sure you’re not mistaken. Many sports watches also calculate cadence, but for the sake of simplicity of experiment, you can use the old-fashioned way and then compare with the clock.

Try not to subconsciously increase the cadence while taking measurements, just relax and run as usual.

How to improve cadence

Start with a 5% goal. As with many principles in running, a slow start is the key to long-term success. Start by increasing your cadence by 5%, and then, when you feel comfortable, you can work on increasing it by another 5%.

For example: if your current cadence on a long run at an easy pace is 156 strides per minute, aim for 164. This will seem more achievable than jumping right off the bat at 180 strides.

Will an increase of only 5% be effective? Research argue that yes: even this modest gain can significantly reduce the stress on the knees and hips.

Don’t try to run faster, over time it will happen on its own.

Set aside some time to work on cadence. Don’t devote your entire workout to cadence, instead try increasing your cadence for 1–2 minutes, then relax and just run in your usual rhythm for a few more minutes. Do some of these repetitions. When you start to feel comfortable with the new frequency, increase the time or distance of the interval.

Pay particular attention to the cadence as fatigue sets in. At the time of fatigue, a decrease in running cadence is usually directly correlated with a drop in speed and poor running technique, as well as an increased risk of injury.

Use a metronome. A good way to train your body to increase cadence is to practice running using a small digital metronome set to a specific cadence (desired cadence). Try running a short distance first to match your steps with the beep without increasing your pace. It will seem strange, even slightly unnatural, but over time you will get used to the increased rhythm.

Add custom workouts to improve cadence. Downhill sprints are great for improving your running form and increasing your cadence. Find a hill with a gentle slope of about 150-200 meters. At the end of an easy run, do four to six intervals downhill. Accelerate as you run, reaching maximum speed at the end of the hill. Run upstairs slowly, do a few repetitions.

Various jumps will also be useful: on one leg (from 5 to 30 touches per leg), and through the rope – on one and two legs, 5-30 touches.

Be patient. You will begin to experience the benefits of running at a higher cadence within 2-4 weeks of adapting. Although it can take up to six months for a full cadence correction, most runners experience significant changes in as little as three months.

However, the longer you run with lower cadence, the longer it will take to correct technique mistakes, so patience is key.